In the researched medical ward the average number of patients per registered nurse was high, and only a third of the overall nursing hours were conducted by nurses with a bachelor's degree. Although, the number of staff did not deviate from that expected in European hospitals , the observed staffing levels could provoke rushed judgments about low quality of care. However, it should be noted that in the observed hospital the management calculates the number of registered nurses and nursing technicians together , ignoring evidence on higher nurse staffing levels being reflected in better patient outcomes . With the use of two profiles of nursing staff, the productivity levels, number of nurse working hours and nurse–patient ratios appear to be good. But this hospital is employing cheaper nursing technicians instead of registered nurses, and this low-cost approach ignores actual patients care needs, actual unit occupancy rates, and staff competences and, as a consequence, the graduate staff are overloaded. This study showed also that patients were more satisfied when the proportion of baccalaureate nurses in the nursing workforce was higher.

Calculating Work Hours Per Patient Day While these results support the findings of previous studies , there is limited evidence correlating hospital nurse staffing with patient satisfaction in the literature . Research reports positive patient outcomes when staffing levels allow a maximum of six patients to one registered nurse on a medical ward . Similarly, other research finds that more patients per nurse result in higher rate of care left undone . The shift to value-based care is just one of many fundamental changes happening in healthcare today. Healthcare organizations across the continuum are challenged to increase productivity AND reduce costs while maintaining proper staff levels to meet patient needs and compliance requirements. Hours per patient day is a common industry expression used to trend the total number of direct nursing care hours , compared to the number of patients as the HPPD ratio.

Using a the "nursing hours per patient day" is a way to monitor and improve quality of care and service. And in many states, hospitals, clinics, acute care facilities, long-term care and senior living facilities must report the HPPD data to the Department of Public Health. OSHPD's Hospital Disclosure Report measures employment in terms of productive hours for each of RNs, LPNs, unlicensed aides/orderlies, management and supervision, administrative and clerical, and other labor categories. Most hospitals use their payroll system, not their actual unit-level staffing grid, to complete the survey, and thus the data are subject to errors that might exist in any payroll system. For example, hospitals might not consistently measure hours worked by nurses normally assigned to one unit but "floated" to another. The number of patient days or services provided in each revenue unit is reported, enabling calculation of hours per patient day, hours per patient discharge, and/or hours per service provided.

Unit types can be aggregated or examined separately (e.g., HPPD for medical–surgical acute care only). The NHPPD is calculated by dividing the total number of productive hours provided by all nursing staff , licensed practical nurses , and unlicensed assistive personnel with direct care responsibilities by patient days. The NHPPD is the most widely used nurse staffing measure in most studies (Min & Scott, 2016;Van den Heede et al., 2009).

Skill mix is defined as the proportion of total nursing hours provided by RNs, compared to LPNs, and UAPs available for patient care during a nursing shift . Correlations between the AHA and OSHPD datasets for inpatient days and RN employment were high overall, at least 0.9. The means of RN and LPN employment were not statistically significantly different, while computed hours per patient day were statistically different in the OSHPD and AHA datasets. Most hospitals provide the staffing data to OSHPD and AHA from payroll systems, which might contain several types of measurement error.

First, these systems do not delineate direct patient care from nondirect care in productive staff or hours, and thus overestimate the amount of direct nursing care received by each patient. For example, a nurse might change the unit to which s/he is assigned, without a change in pay, and this change may not be reflected in the payroll data in a timely fashion. We used a hierarchical four-grade nursing care classification system to assess nursing care levels for patients at different acuity levels. This system identifies the staffing levels required to achieve appropriate nursing care, although unfortunately it is not used in practice yet. When we compared the actual nursing levels, the conventional patient-to-nurse ratio and the nurses needed on the basis of patients' classification, we found severe shortages. Individual patient requirements were not respected, as a 38% shortage of registered nurses was measured.

Therefore, nursing staff requirements should be considered as a predictor of the quality of nursing services , and having enough nurses to meet patient needs could be reflected in higher patient satisfaction with nursing care . The panel reviewed current staffing ratios of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nursing assistants, and concluded the current levels are inadequate. Seventeen out of the 30 conference participants endorsed a final staffing recommendation that established 4.55 total nursing hours per resident day as a minimum threshold. Noting that nursing management and leadership are central to providing a high quality of care in nursing facilities, the panel also recommended the director of nursing in nursing facilities have a minimum of a bachelor's degree.

Associations between comprehensive nurse staffing characteristics and patient falls and pressure ulcers were examined using negative binomial regression modeling with hospital- and time-fixed effects. Rates of patient falls and injury falls were found to be greater with higher temporary registered nurse staffing levels but decreased with greater levels of licensed practical nursing care hours per patient day. Some researchers have argued that hours per patient day is the most precise measure of the amount of nursing care provided to patients (Budreau et al. 1999). However, hours per patient day do not accurately measure the impact of admissions, discharges, and transfers on the workload of nurses. Unruh and Fottler have demonstrated that nurse staffing measures that do not adjust for patient turnover underestimate nursing workload and overstate RN staffing levels.

While prospective unit-level databases such as CalNOC often include measures of admissions, discharges, and transfers, administrative databases do not include such measures. Many researchers and health care leaders want to measure nurse staffing according to the workload of each nurse, although "workload" does not have an agreed-upon definition. Most hospitals can easily report the average number of productive nursing hours per patient day ("hours per patient day" or HPPD), because they keep data on nursing hours and patient days. Based on an analysis of 1999 cost report filings, all of Connecticut's nursing facilities licensed as CCNHs exceed the minimum nursing-staff-to-resident-day ratios established under the regulations. Although the regulations require 694 annual minimum nursing staff hours for CCNHs, all nursing homes licensed under the CCNH category had 754 annual hours or more per bed in direct care staffing.

Based upon the data contained in the cost reports, there was an average of 1,435 direct care hours per resident per year; more than double that required under the regulations. In this observational study we analysed retrospectively the control group of a stepped wedge randomised controlled trial concerning 14 medical and 14 surgical wards in seven Belgian hospitals. All patients admitted to these wards during the control period were included in this study.

In all patients, we collected age, crude ward mortality, unexpected death, cardiac arrest with Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation , and unplanned admission to the Intensive Care Unit . A composite mortality measure was constructed including unexpected death and death up to 72 h after cardiac arrest with CPR or unplanned ICU admission. Every 4 months we obtained, from 30 consecutive patient admissions across all wards, the Charlson comorbidity index. The amount of nursing hours per patient days were calculated every day for 15 days, once every 4 months. Data were aggregated to the ward level resulting in 68 estimates across wards and time.

Linear mixed models were used since they are most appropriate in case of clustered and repeated measures data. To assess the key variables used in research on nurse staffing and patient outcomes from the perspective of an international panel. A Delphi survey (November 2005-February 2006) of a purposively-selected expert panel from 10 countries consisting of 24 researchers specializing in nurse staffing and quality of health care and 8 nurse administrators. Each participant was sent by e-mail an up-to-date review of all evidence related to 39 patient-outcome, 14 nurse-staffing and 31 background variables and asked to rate the importance/usefulness of each variable for research on nurse staffing and patient outcomes. In two subsequent rounds the group median, mode, frequencies, and earlier responses were sent to each respondent.

Twenty-nine participants responded to the first round (90.6%), of whom 28 (87.5%) responded to the second round. The Delphi panel generated 7 patient-outcome, 2 nurse-staffing and 12 background variables in the first round, not well-investigated in previous research, to be added to the list. At the end of the second round the predefined level of consensus (85%) was reached for 32 patient outcomes, 10 nurse staffing measures and 29 background variables.

The highest consensus levels regarding measure sensitivity to nurse staffing were found for nurse perceived quality of care, patient satisfaction and pain, and the lowest for renal failure, cardiac failure, and central nervous system complications. Nursing Hours per Patient Day received the highest consensus score as a valid measure of the number of nursing staff. As a skill mix variable the proportion of RNs to total nursing staff achieved the highest consensus level. Both age and comorbidities were rated as important background variables by all the respondents. These results provide a snapshot of the state of the science on nurse-staffing and patient-outcomes research as of 2005. The results portray an area of nursing science in evolution and an understanding of the connections between human resource issues and healthcare quality based on both empirical findings and opinion.

Metrics such as hours per patient day and nursing hours per patient day , referred to by Carter as CHPPD, have been used for decades in the US to examine nursing productivity both within and between hospitals. They are also used to determine staffing levels based on national or regional benchmarks and establish budgets for nursing departments. NHPPD usually refer to qualified nurses in the US, so may include only RNs with degrees or both RNs and those with older diplomas and/or licensed practical nurses. NHPPD are also used in several states in Australia and are usually used to describe qualified nurses only.

This is why it is important to understand which staff are included before accepting staffing data. The program review committee compared the minimum regulatory nursing staff requirements to actual hours of nursing staff reported by facilities in its Medicaid cost reports. There are several caveats attached to the data used for an analysis of the distribution of nursing staff among Connecticut's nursing facilities.

First, the number of hours reported for RNs, LPNs, and nurse aides by facilities is self-reported and not audited by DSS. In addition, there are no uniform definitions for reporting on nursing staff hours. Thus, while some facilities may report paid hours, which include any vacation, sick, and personal time accrued, others might report actual hours worked. Third, nursing staff hours are reported on an annualized basis, but daily, weekly, and monthly nursing staff fluctuations may vary considerably. Finally, data were available for only 226 facilities out of the 253 licensed CCNHs, and estimates are based on an average 95 percent occupancy rate, rather than a facility's actual occupancy. Decisions about the adequacy and appropriateness of nurse staffing have long been based on functionally outdated industrial models that focus on work sampling and time-and-motion studies conducted in semi-simulated settings.

Even today, the common method of staffing nursing units or identifying the staffing mix in hospitals is by identifying budgeted Nursing Care Hours per Patient Day. A traditional measure of nursing productivity, "nursing hours per patient day has never been satisfactory because 'patient day' as a measure of nursing output takes neither patient acuity nor quality of nursing care into accou nt". . The survey requested that hospitals provide data for a representative medical–surgical unit in the hospital. Survey questions focused on nursing hours worked on that unit, discharges and patient days on the unit, nurse-to-patient ratios, number of vacancies, and average time to recruit a RN to the unit.

Both hours per patient day and the nurse-to-patient ratio were reported directly by unit managers, enabling a direct comparison of these methods of measuring nurse staffing. Observations suggest that registered nurses need to engage in a great variety of tasks, and spend a great deal of time locating the information needed for individual patients. Health education, clinical references, consulting, and coaching were the least frequent activities in the registered nurses' working days. We were not able to observe a fifth of the registered nurses' activities, as these were done outside the medical ward. These activities could thus not be classified in the observations, but were described by the staff as nursing tasks on other medical units, meetings with management, quality teams, and so on. Moreover, the results show that the patients noticed the individual attention they received from registered nurses while they cared for them, and that their explanations helped them feel more at ease.

Nurses are known to spend more time with patients than other health professionals, and that enables them to show the caring attitude which is sensitive to patients' reports of quality of nursing care . Registered nurses have a wide range of nursing knowledge and good communication skills, are alert to changes in the patients' status and have the competencies needed to do all the activities that arise in nursing care. Nursing technicians have fewer competencies, and care for fewer patients than registered nurses – certain tastes are thus not delegated from registered nurses to technicians, but the vice versa. This could mean that patients would benefit if mixed staffing models, like the one observed in this study, would include more nurses with bachelor's degrees.

The 3.5 DHPPD staffing requirement, of which 2.4 hours per patient day must be performed by CNAs, is a minimum requirement for SNFs. SNFs shall employ and schedule additional staff and anticipate individual patient needs for the activities of each shift, to ensure patients receive nursing care based on their needs. The staffing requirement does not ensure that any given patient receives 3.5 or 2.4 DHPPD; it is the total number of actual direct care service hours performed by direct caregivers per patient day divided by the average patient census.

Table 2 summarizes the critical care and medical–surgical nurse staffing and patient days data reported by CalNOC and OSHPD. OSHPD reports a greater number of RN and LPN hours as well as patient days, and all differences are statistically significant. The greater number of nursing hours reported by OSHPD is consistent with OSHPD's productive hours including non-direct-patient-care hours, which may include RNs in special roles such as clinical specialists or infection control managers.

The correlations between RN hours, LPN hours, and patient days are relatively high, ranging from 0.73 to 0.92. The correlations are higher for critical care than for medical–surgical care. Inpatient care unit does not include any hospital-based clinic, long-term care facility, or outpatient hospital department. "Staffing hours per patient day" means the number of full-time equivalent nonmanagerial care staff who will ordinarily be assigned to provide direct patient care divided by the expected average number of patients upon which such assignments are based. "Patient acuity tool" means a system for measuring an individual patient's need for nursing care.

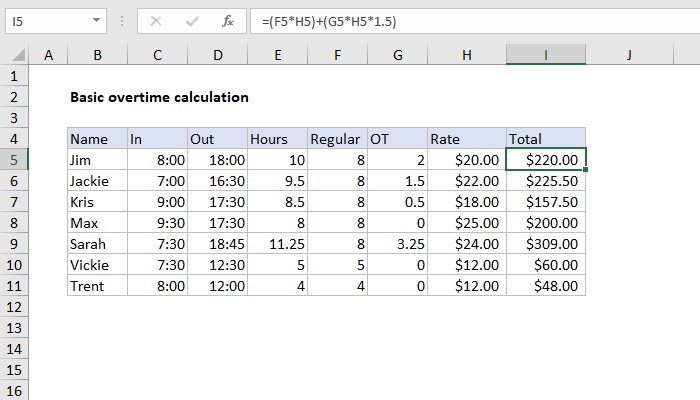

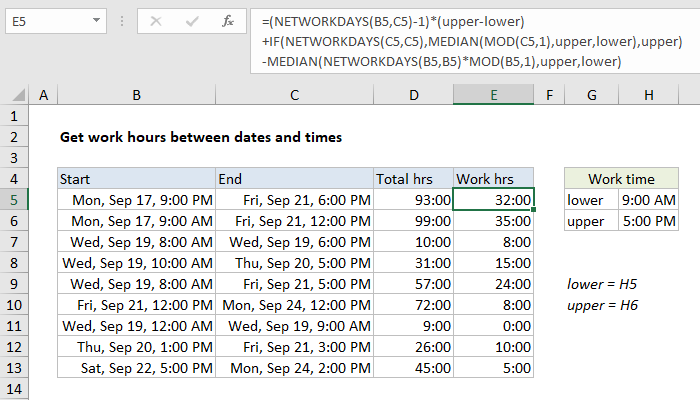

Currently, the Nursing Care Hours per Patient Day formula is the unit of analysis that determines staffing requirements in hospitals. It is a calculable formula that is used as a method of staffing and for budgeting nursing hours . Nursing Care Hours per Patient Day are calculated by multiplying the number of staff delivering direct nursing care by the hours worked during the shift and then dividing that number into the average daily census at a specific designated time. For the purposes of this study, the midnight census was chosen as the designated time. Nursing Care Hours per Patient Day were studied and the data from both Quarters under review were analyzed and compared.

The CalNOC data are less widely dispersed than the OSHPD data for the matched set of hospitals, suggesting that the CalNOC data might contain less measurement error. Nursing hours were on average higher in the OSHPD data than in CalNOC, likely because OSHPD data include nurse staff time spent on activities other than patient care. As a result, the distribution of nurse staffing per patient day is different between these datasets, with the CalNOC data producing somewhat lower hours per patient day than the OSHPD data.

The correlations between estimates of hours per patient day are low, at 0.22 for total nursing hours and 0.32 for RN hours. A relationship between staffing and quality of care in nursing homes is inherently logical. However, the correlation is difficult to demonstrate because of the complexities in defining and measuring quality, the lack of valid nursing staff data, and the differences in residents' acuity levels among facilities. The purpose of the analysis was to determine if facilities that received a high number of deficiencies reported less staff per resident day than those with zero or only one deficiency.

In fact, according to published studies hospital nurses spend from 7.3% to 54.2% of their time on direct patient care, from 0% to 59% on indirect care, and from 14% to 17% on personal time . Patient satisfaction is influenced by factors identified at the patient level along with nurses' kindness and competence with regard to performing technical procedures . When items in the instrument represent patients' perceptions, there are no criteria against which criterion-related validity could be tested .

Aim To describe nurse‐specific and patient risk factors present at the time of a patient fall on medical‐surgical units within an academic public healthcare system. Background The incidence of falls can be devastating for hospitalized patients and their families. Few studies have investigated how patient and nurse specific factors can decrease the occurrence of falls in hosptials. Method In this retrospective cohort study, data was gathered on all patients who experienced a fall during January 2012‐December 2013.

Results Falls were reduced dramatically when the number of nurses on the unit increased to five or six. Patient falls occurred most often when either the least experienced or most experienced nursing staff were providing care. Conclusion Patient falls in hospitals can be influenced not only by patient specific factors, but by nurse staffing and experience level. Implications for nursing management Findings from this study highlight factors which may contribute to hospital‐based falls prevention initiatives, and are amenable to nursing management decisions. 2 The tendency is for nursing managers to fall back on ratio and unit layout and patient location information to make patient assignments. 6 Objective evaluation of patient acuity and needs has shown to improve nurse perception of assignments as more equal and more able to provide safe quality care.

The program review committee believes the minimum nursing staff ratio suggested in HCFA's study is based on the most comprehensive and defensible research to date. Furthermore, the establishment of minimum nursing staff standards does not negate the federal and state requirements that nursing facilities provide adequate nursing staff to meet residents' needs. Minimum staffing thresholds merely establish a floor below which a facility cannot drop. An analysis from the Journal of Emergency Nursing found that a calculation of hours per patient visit was the most frequently used method for determining staffing in the ED. This method requires dividing the number of actual paid hours by the total number of ED visits to calculate the number of staff hours per year. The authors pointed out that this type of system fails to take a few critical factors into consideration, including patient acuity, length of stay, and nursing workload.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.